On the 1st of November 2017, the Bank of England voted to raise interest rates for the first time in more than ten years. After such a long period without any increase, this news inevitably grabbed the headlines but the new rate of 0.5% still remains the second lowest on record. The net effect of this on the housing market is likely to be very small.

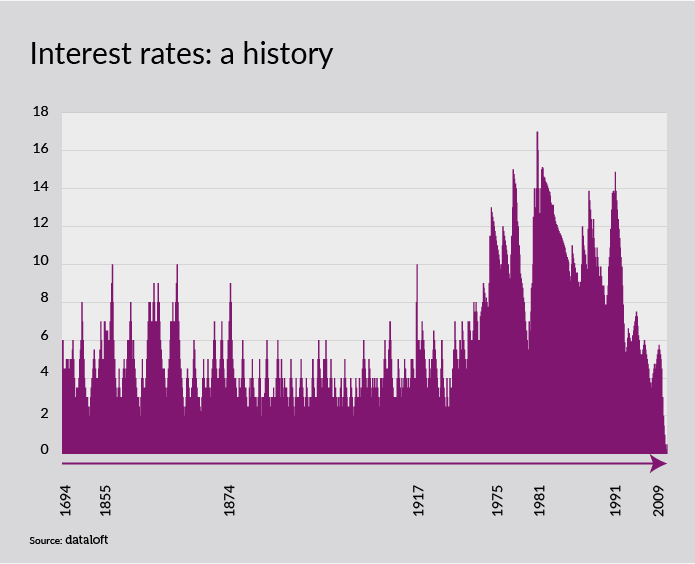

In fact, rates were at 0.5% during the whole period from March 2009 to August 2016 – set exceptionally low in an attempt to stimulate the economy in the wake of the financial crisis. Until the last quarter of 2008, interest rates had never been below 3% and for nearly ten years before that they had averaged 4.9%. Looking further back to the mid-1990s interest rates averaged 6.5% between December 1994 and December 1998. In the 1970s, interest rates were never in single digits, averaging 11% between 1973 and 1977, with highs of 15% in October 1976 - when the government was fighting high levels of inflation.

While a number of banks and building societies have already announced that they will pass on the rate increase to borrowers, the impact of a quarter per cent rise on the pockets of most home owners, will be minimal. Indeed, UK Finance report that, over the last two years, more than 90% of new mortgage and re-mortgage loans have been on fixed rate deals. Of all outstanding mortgage loans, more than half are now on fixed rate deals.

For the five million borrowers on variable rate mortgages, some increase in their monthly mortgage is to be expected. Nationwide estimate that the 0.25% rise will raise the mortgage bill for home owners with a £175,000 mortgage on their base mortgage rate, by £22 per month.

The Mortgage Market Review, introduced in 2014 should mean that borrowers are better prepared for an increase than they might have been in the past. UK Finance estimate that, of all mortgages granted since 2015, 92% have been stress tested against an interest rate of at least 3% higher than their current rate.

Nevertheless, some economic commentators have suggested that the timing of this rise in interest rates is very odd given all the uncertainty that still surrounds the Brexit negotiations. There is a risk that the hike could be interpreted as part of a cycle of interest rate hikes which could knock consumer confidence at a vulnerable time in the UK’s economy.

The housing market is highly sensitive to interest rate rises and the Bank of England has been careful to reassure the market that only ‘very gradual’ further increases will be required over the next three years, edging towards 1% by the end of 2020.

Indeed, some argue that the rate rise should be viewed as a reflection of the strength of the economy where growth has been supported by resilient consumer confidence, a stronger world economy and small loosening of fiscal policy.

And let’s remember the savers, especially those saving for a deposit to buy a home. Any rise in interest rates, however small, is good news for savers. Some see this increase as primarily a timely warning to consumers who might otherwise be tempted to abandon savings and turn to borrowing in order to counter low wage growth and rising inflation. For the UK housing market, this is unlikely to have any discernible impact on prices or demand as we head into the low season. The Autumn Budget, which is expected to bring some concessions on stamp duty for first-time buyers, might merit bigger headlines.